Navigating Multiple Myeloma: The Critical Importance of the First 90 Days

Navigation Strategies to Improve Care, with Expert Commentary by Peg Rummel, RN, MHA, OCN, NE-BC, HON-ONN-CG

Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators: Mission and Vision

The mission of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+) is to advance the role of patient navigation in cancer care and survivorship care planning by providing a network for collaboration and development of best practices for the improvement of patient access to care, evidence-based cancer treatment, and quality of life during and after cancer treatment. Cancer survivorship begins at the time of cancer diagnosis. One-on-one patient navigation should occur simultaneously with diagnosis and be proactive in minimizing the impact treatment can have on quality of life. In addition, navigation should encompass community outreach to raise awareness targeted toward prevention and early diagnosis, and must encompass short-term survivorship care, including transitioning survivors efficiently and effectively under the care of their community providers.

The vision of AONN+ is to increase the role of and access to skilled and experienced oncology nurse and patient navigators so that all patients with cancer may benefit from their guidance, insight, and personal advocacy.

AONN+ would like to acknowledge the efforts and dedication of oncology nurse navigator Peg Rummel, RN, MHA, OCN, NE-BC, HON-ONN-CG, who dedicated her knowledge, time, and efforts to enhance the care of patients with cancer through the development of this guide.

The endorsement mark certifies that the information presented in educational seminars, publications, or other resources is reliable and credible.

Each year in the United States, approximately 35,000 people are diagnosed with multiple myeloma, and more than 12,000 patients die of the disease.1 Since 1990, the incidence has risen at least 40%, with relatively higher rates among those who are black, older, male, or with a family history of the disease.2 Coincidentally, 5-year survival in the United States has doubled, largely due to the introduction of targeted therapies, now used in triplet or even quadruplet regimens.2,3

With these increasingly safe and effective treatment protocols, myeloma has become—for many patients—a chronic disease manageable with continuous therapy, allowing for years of survival with a good quality of life.4 To achieve such outcomes, however, patients must first undergo comprehensive diagnostics for disease staging and identification of risk factors, then adhere closely to their personalized treatment plan.5,6 During the first 90 days of a myeloma diagnosis, patients and caregivers are processing a high volume of new information, psychologically adjusting to this potentially life-altering diagnosis, and possibly facing barriers to care. In addition, most patients with myeloma are older and therefore often managing comorbidities, which can increase the risk of poor adherence.7,8 This environment highlights the critical role played by oncology nurse navigators, who can coordinate a multidisciplinary care team while educating patients and guiding them through their treatment journey.

This article will update oncology nurse navigators on the myeloma landscape, including a review of the disease state, diagnostic tests, treatment options, and navigation strategies. Each evidence-based section is followed by expert commentary from oncology nurse navigator Peg Rummel, RN, MHA, OCN, NE-BC, HON-ONN-CG, who speaks from 25 years of clinical experience with multiple myeloma.

Ms Rummel: When I first started in the field, there weren’t a lot of treatments for patients with myeloma. Now, patients have a lot more options, and over the past 2 years, the landscape has just blossomed with FDA approvals. With these new treatments, we’re seeing patients continue therapy instead of going straight to transplant, and they’re living much longer.

Disease Overview

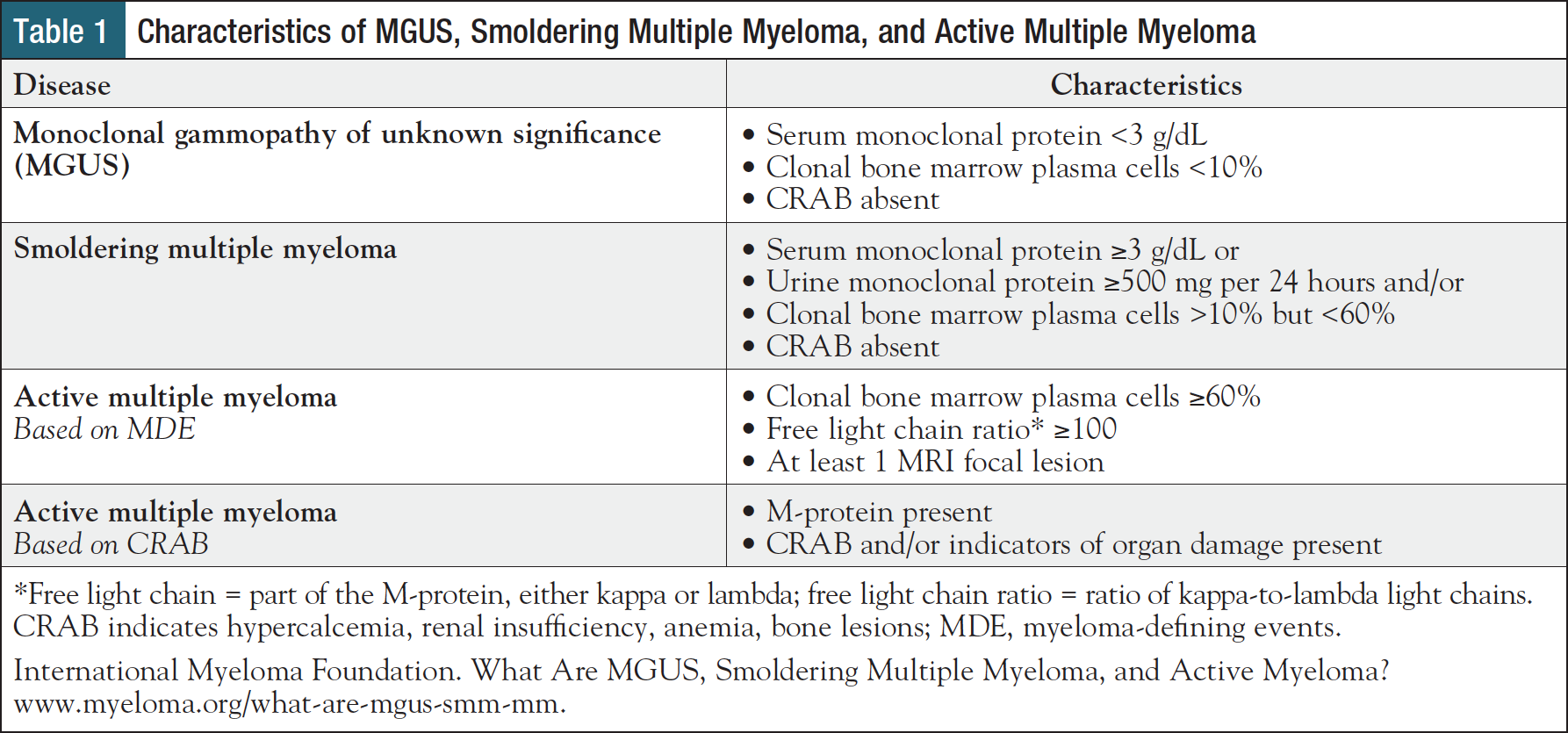

Multiple myeloma is a malignant cancer of plasma cells in the bone marrow in which affected cells (ie, myeloma cells) overproduce monoclonal protein (M-protein), leading to a constellation of physiologic abnormalities known as the “CRAB” criteria: hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, and osteolytic bone lesions.2,9 Before reaching this symptomatic stage, also known as “active” or “full-blown” multiple myeloma, patients pass through 2 stages of premalignancy: monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS) and smoldering multiple myeloma, both of which are asymptomatic and typically discovered incidentally during laboratory testing.10,11

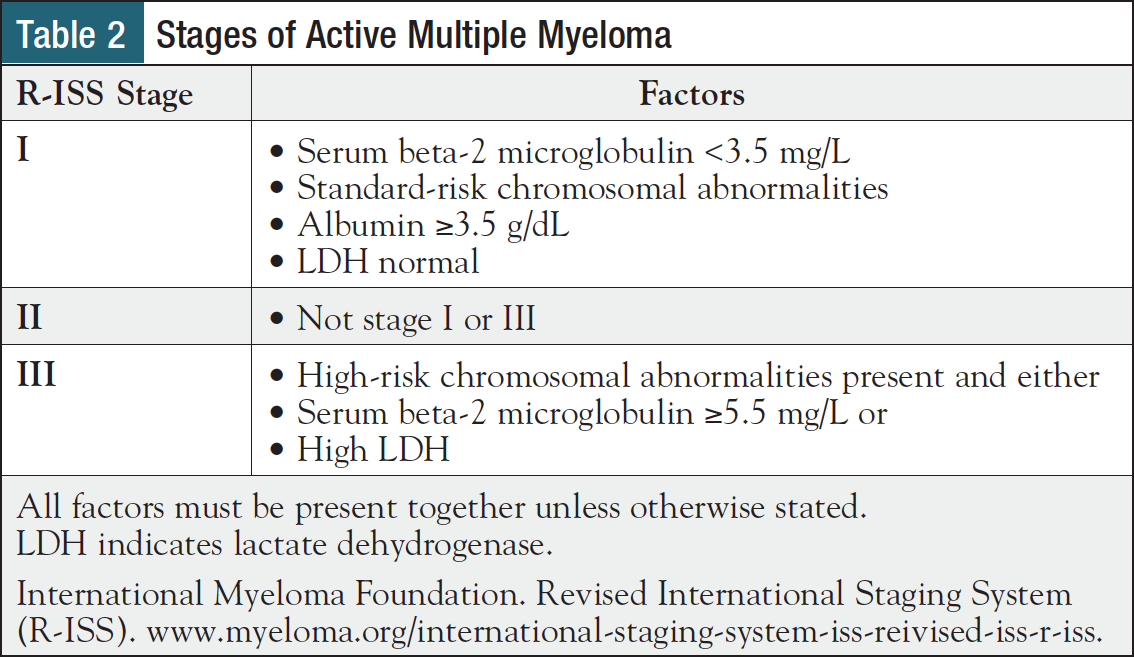

These 3 disease types are differentiated by levels of M-protein and its component parts in blood and urine, the proportion of bone marrow cells that are plasma cells, CRAB criteria, and myeloma-defining events (MDEs) (Table 1).12 Patients with active multiple myeloma are staged according to the Revised International Staging System (R-ISS), which incorporates blood levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), beta-2 microglobulin, albumin, and presence or absence of high-risk cytogenetics (Table 2), all of which are covered in greater detail in the next section.5

Ms Rummel: With multiple myeloma, there are so many stages. There’s MGUS, there’s smoldering multiple myeloma, there’s full-blown multiple myeloma, and each one has its own treatment paradigm that’s constantly changing. It can be difficult for patients to understand that they may have MGUS or smoldering myeloma but we’re only going to be observing them and watching their biomarkers until they convert, or they feel that they need more treatment, and that they could be in that watch-and-wait stage for a long time.

I explain that observation is a good thing, and that we want to save the big guns for later—for when they’re really needed. A lot of my early conversations with patients are about reinforcing the physician’s plan and educating them that our decisions are based on years of research. We have all sorts of clinical trials that show which treatments are appropriate for patients in each stage of their disease.

Common Diagnostics

Patients with myeloma or myeloma-related blood disorders undergo an array of diagnostics to identify their disease type and stage, determine prognosis, and guide treatment selection.3,5 Accurate characterization of disease is critical because treatments vary widely—from periodic observation for patients with MGUS and low-risk smoldering myeloma to personalized intervention for patients with high-risk smoldering myeloma or active myeloma.3,5 Common diagnostics and associated rationale are reviewed below.

- Complete blood count5: An excess of myeloma cells in the bone marrow can lead to reductions in various circulating blood cells, including platelets (thrombocytopenia), white blood cells (leukopenia), and most commonly, red blood cells (anemia), the latter of which constitutes 1 of the CRAB criteria.

- Chemistry panel5: Active myeloma can cause a variety of derangements in blood that are indicative of disease severity. Two of the CRAB criteria—hypercalcemia and renal insufficiency (high creatinine)—are identifiable on a chemistry panel. In addition, findings may uncover low albumin or high LDH, both of which suggest more aggressive disease.

- Beta-2 microglobulin13: Myeloma cells produce the protein beta-2 microglobulin. Elevated levels in blood, typically included in blood chemistry results, suggest more advanced disease.

- 24-hour urine protein13: Total protein level in urine is associated with tumor burden. The tests below quantify and characterize proteins in urine, offering further insights at diagnosis and during treatment monitoring.

- Urine protein electrophoresis13: This test measures urinary M-proteins and their component part, light chains, also called Bence-Jones proteins. Patients with more Bence-Jones proteins in urine have a higher risk of kidney damage

- Urine immunofixation13: This test characterizes the type of M-proteins in urine

- Serum quantitative immunoglobulins13: This test identifies and quantifies immunoglobulins (also called antibodies) in blood, including immunoglobulin (Ig) A, IgD, IgE, IgG, and IgM. A high level of one antibody can indicate myeloma, as abnormal plasma cells are overproducing this type of protein. These overabundant antibodies are called M-proteins.

- Serum protein electrophoresis13: This test quantifies the level of M-proteins in blood

- Serum immunofixation13: This test characterizes the type of M-proteins in blood as either kappa or lambda

- Free light chain analysis5,13,14: Free light chain analysis measures the amount of kappa and lambda light chains separate from M-protein heavy chains in blood, offering prognostic and diagnostic value. In health, kappa and lambda light chains are found in approximately equal proportions, but in myeloma, one may be produced more than the other. For example, a high ratio of kappa-to-lambda light chains is one way that active myeloma may be diagnosed (Table 1).

- Bone survey/computed tomography (CT)13: All bones are screened for lytic lesions, using either radiography, or more commonly, CT.

- Bone marrow biopsy/aspiration5: Taken from the pelvis, or other sites, these samples are used to perform a range of tests that identify and characterize myeloma, including immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, fluorescence in situ hybridization, and cytogenetics.

- Cytogenetic testing3,5: Cytogenetic tests identify a range of chromosomal abnormalities in both normal bone marrow cells and myeloma cells. Certain abnormalities are associated with high-risk disease. “Double-hit” myeloma is defined by the presence of 2 high-risk abnormalities, while “triple-hit” myeloma is defined by 3 or more high-risk abnormalities. Cytogenetic findings can help determine prognosis and guide treatment selection.

Ms Rummel: As the saying goes, “Tissue is the issue,” because we need a bone marrow biopsy, plus other lab work, to figure out what we’re dealing with. When I first meet a patient, I just try to understand the diagnostic testing involved, and what the results mean, because that determines the treatment. In the first 90 days, it’s all about getting a diagnosis, looking at the plasma cell count, looking at the genetics, and getting the patient started on a treatment that will bring their levels down.

Keep in mind that new therapies for myeloma—including immunotherapies and oral agents—come with different safety profiles than the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy. You need to understand what the drugs are, which regimen the patient is on, and you need to be able to answer the patient’s questions about that regimen. As an oncology professional, it’s important to keep up to date with these new treatment options.

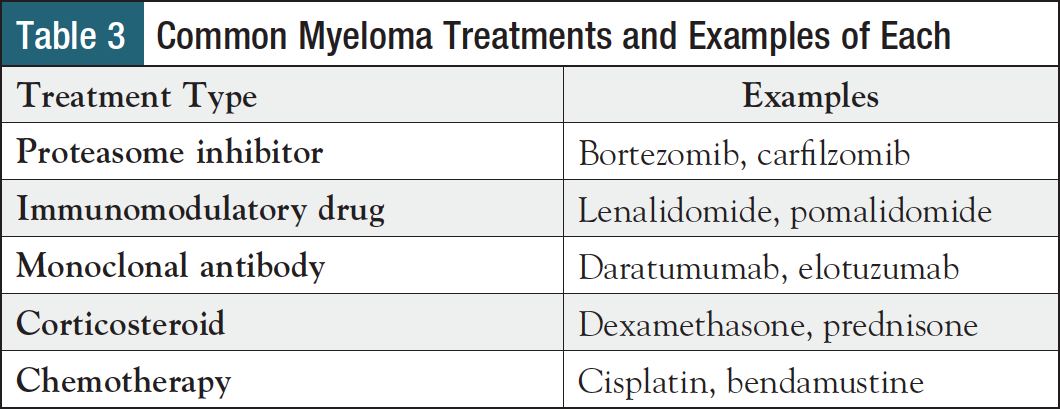

Treatment Planning

Over the past 2 decades, new therapies have significantly extended multiple myeloma survival and have become mainstays across lines of treatment, from initial diagnosis to the relapsed/refractory setting.15,16 While doublet combinations were previously the norm, patients are now more likely to receive a triplet regimen, with 62% of patients receiving a 3-drug combination for first-line therapy.16 More recently, 4-drug combinations have been gaining ground and are recommended for first-line treatment of newly diagnosed, transplant-eligible, high-risk myeloma.3 Table 3 offers an overview of common types of agents used to treat myeloma, and examples of each.

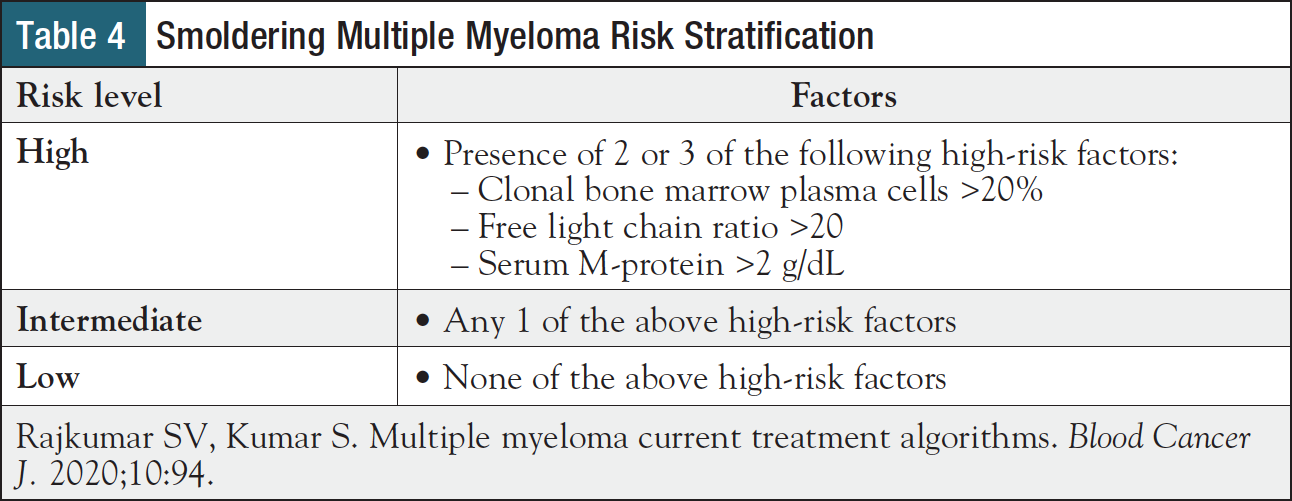

Treatment selection first depends on type of disease. Unless a patient is participating in a clinical trial, MGUS is monitored without treatment, whereas smoldering myeloma may be treated if certain high-risk disease factors are present (Table 4).3,17 Specifically, patients with high-risk smoldering myeloma should be offered lenalidomide with or without dexamethasone or enrollment in a clinical trial.

Treatment decision-making for active multiple myeloma involves a more complex array of factors, including eligibility for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), risk level, and prior treatments.3 ASCT eligibility is typically determined by comorbidities, performance status, and age.3 Treatment decisions also account for patient age and comorbidities, as well as overall tumor burden and cytogenetic abnormalities, the latter of which are incorporated into the R-ISS (Table 2).1,18 Clinical trial participation should be considered in each stage of the disease process.3

Due to a broad range of therapeutic options and clinical considerations, a comprehensive guide to myeloma treatment planning is beyond the scope of this article; however, 2 common clinical scenarios are considered below to give a sense of how treatment options are personalized.3

- Newly diagnosed, transplant-eligible patient: This patient would most likely receive first-line therapy with either a triplet or quad combination, depending on risk factors. For example, an individual with standard-risk myeloma could receive 3 to 4 cycles of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone; they would then receive early ASCT and maintenance therapy with lenalidomide. Alternatively, after 3 to 4 cycles of the triplet, they could undergo stem cell collection, then receive 5 to 8 more cycles of the same triplet before receiving lenalidomide maintenance therapy, with ASCT at relapse. In contrast, an individual with high-risk myeloma is more likely to receive a quad regimen involving the above 3 agents, plus daratumumab, a monoclonal antibody, followed by early ASCT and bortezomib-based maintenance therapy

- First relapse: At first relapse, therapy selection depends on whether the patient is refractory to lenalidomide. Nonrefractory patients typically receive a triplet of daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone, or, if frail, a triplet that substitutes ixazomib for daratumumab. Patients who are refractory to lenalidomide may receive a greater variety of triplets, such as daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, or, if frail, ixazomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone

Readers seeking a more comprehensive roadmap to myeloma treatment can rely on the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines,19 or, for a more succinct guide to risk stratification and treatment algorithms, a recent review by Rajkumar and Kumar.3

Although the myeloma landscape is rapidly changing, one thing will stay the same: treatment planning should always incorporate each patient’s personal values and goals, as these are essential factors in patient satisfaction and adherence.20

Ms Rummel: Even though cytogenetic abnormalities are important in treatment selection, when you’re talking about results with patients, try not to get too bogged down in the details, because you can really confuse people. Instead, patients need to know that they have a high plasma cell count in their bone marrow, so they need treatment, and here are the options we can treat them with. When you’re talking about specific treatments, focus on the basics, like common side effects, number of cycles, and those types of things. We need to keep it simple. Patients get so overwhelmed that they only hear about 10% of what we tell them.

Improving Adherence and Navigating Psychosocial Impacts

Over the years, treatments for multiple myeloma have become more effective, but as more drugs are being used in combination, regimens have also become increasingly complicated, potentially lowering treatment adherence.21 This complexity is magnified with oral agents for myeloma, such as proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, which are typically taken at home, making them more challenging for providers to monitor and easier for patients to discontinue.21

According to a recent study, 30% of myeloma patients are nonadherent to oral agents.22 Patients may stop taking their medications for a variety of reasons, including toxicity (perceived or actual), polypharmacy, lack of social support, cognitive impairment, use of specialty mail order pharmacies, financial cost, and poor provider–patient communication.21 Oncology nurse navigators need to be aware of these barriers, and through efforts early in the treatment journey equip patients with knowledge that will improve their chances of remaining adherent through the first 90 days and beyond. Patient expectations are an integral part of this process because patients with cancer who maintain accurate expectations tend to be more adherent, and they also experience fewer side effects and maintain a better quality of life.23

When setting expectations, myeloma patients should be informed that a range of diagnostics are needed, especially early on, and that it’s normal to feel like many tests are being performed, and that a high volume of information is being discussed. Patients should be reassured and encouraged to voice their concerns and ask questions; they should also write down questions and concerns that arise after each visit.

Navigators should also set reasonable timelines for patients, including expected duration of therapy, time needed to adjust to medications, and time to find a combination that balances efficacy and tolerability. When patients first start therapy, rapid communication should be encouraged, particularly if patients believe they are having adverse events; in such a scenario, patients should know that further investigation may be needed to determine if new symptoms are medication- or disease-related, and if medication-related, which agent is causing the problem. To further increase adherence, patients should know that there is a strong link between treatment adherence and optimal outcomes.6

Organization is also critical for medication adherence, particularly among patients already taking medications for comorbidities. Navigators should therefore educate patients about ways to take the right medications at the right times, including use of calendars, pill organizers and dispensers, and for the more technologically inclined, smartphone reminder apps.

Navigators should also consider enlisting the help of caregivers, family members, and friends who can be an invaluable part of a patient’s support system, both from a practical and a psychosocial perspective. Keep in mind that a patient’s place in their treatment journey—from recently diagnosed with MGUS to managing active myeloma—poorly predicts their mental health.24 While physical health–related quality of life tends to decline as myeloma progresses, mental health–related quality of life, psychological distress, and anxiety are a burden for many patients, regardless of disease stage.24

Although caregivers, family members, and friends can be a source of emotional strength, they themselves can also be affected on an emotional, social, spiritual, and physical level.25 These broad impacts, felt by both patients and their social group, can lead to a wide variety of issues, including disruptions in family organization and altered relationships.25 And since every family is unique, methods of best supporting patients and their loved ones may take some time to uncover.25 Social workers, therapists, and third-party patient advocacy organizations may be needed to help navigate this complex psychosocial environment.

Ms Rummel: It’s important to meet patients where they are. Early on, I try to find out their expectations and their understanding of the treatment paradigm. I ask a lot of questions. Are they expecting a cure, or to maintain their quality of life? Do they have a specific event that they want to make it to, like a child’s wedding or the birth of a grandchild?

Remember that every patient is different, and things can change throughout the treatment journey. Maybe a patient starts working the night shift instead of a day shift, so we need to change their medication schedule so they can sleep. Sometimes it’s a simple fix; other times you need to be creative and think outside the box. Ultimately, patients have more buy-in and are more adherent if they’re part of the process.

If a patient says, “I’ve just had enough of this,” I try to find out why. If they really want to take a break from treatment, I let them know that we need to talk it over with their physician, and that we’ll support them through whatever decision they make. It’s important for patients to know that they can collaborate through shared decision-making with their healthcare team. Patients often feel that they don’t want to be a bad patient or disappoint their doctor, but sometimes it’s okay to say, “I’ve had enough, I’ve been doing this for 15 years, and I just can’t do it anymore.” Our job is to keep communication open and help them move on to the next steps.

Barriers to Care

Patients with multiple myeloma experience barriers to care, such as information barriers, care coordination issues, financial barriers, and transportation concerns.8 Although some of these issues cannot be solved (eg, distance to treatment center), most of them can be addressed. For example, communication may be improved through some of the previously described strategies for setting expectations, which could in turn influence rates of adverse events, possibly reducing rates of treatment discontinuation.23

The survey findings also suggest that financial barriers are common, so navigators should be aware of the various organizations that help manage costs of myeloma, including the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS), CancerCare, the Patient Access Network Foundation, and others.26 Additional social support may be provided by in-hospital social workers and by external patient advocacy groups, such as the International Myeloma Foundation (IMF).26

Ms Rummel: When I do an assessment, I ask questions to really understand each patient’s situation: “Where are you living? What’s your support system? Are you going to have trouble getting back and forth to our treatment center? Are you working, and is this going to impact your ability to work?” I ask about basic needs, like childcare and pet care, housing, and food. I also ask each patient what their primary language is instead of assuming that it’s English. The other thing I ask is, “How do you learn best?”

At the same time, I make sure that counseling or mental health services are available for patients and caregivers. If someone is newly diagnosed, they may not be coping well, or caregivers may not be coping well, and the situation can bring out old issues that need to be addressed for the patient and their caregiver to get through treatment.

It’s important to be aware of the resources that are out there to help. Some of the supports are going to be different depending on location, but the bigger resources that are out there, like LLS and IMF, can help all patients.

Survivorship

Starting early in the treatment journey, oncology nurse navigators need to prepare patients for their transition into posttreatment survivorship, which can be a period of poor communication.27,28 Survivorship is a particularly important aspect of care for patients with myeloma, who are living longer than ever before.

According to the IMF Nurse Leadership Board, myeloma survivorship plans should address 5 areas of concern: health maintenance, bone health, mobility/safety, renal health, and sexual dysfunction.29 Below, each of these categories is accompanied by example subtopics that may be included in a survivorship plan. For a comprehensive review of the subject, see the 2011 guidelines by Bilotti and colleagues.

- Health maintenance: screening and management of comorbidities, comorbidity risk factor education29

- Bone health: dietary counseling, diagnostic monitoring, exercise promotion29

- Mobility/safety: immobility reduction and management, fall risk education and prevention29

- Renal health: kidney disease screening, environmental risk reduction, renal complication management29

- Sexual dysfunction: sexual dysfunction screening, risk prevention, intervention awareness29

Ms Rummel: Survivorship starts at the time of diagnosis. Patients don’t just stop treatment and go into survivorship. Once a patient is diagnosed, they become a survivor, and we work with them through the long haul through all their various treatment paradigms.

We work with them on health maintenance—making sure they’re getting screened for health issues, getting their vaccinations, those types of things, while providing education about bone health and fall risk reduction. Patients also need to understand what their disease-associated risk factors are, like kidney issues and sexual dysfunction. Sexual dysfunction is always a topic that nobody wants to talk about, but we as healthcare professionals need to do a better job of discussing it. We often think that our patients aren’t interested in sex because they’re older, but that is usually not the case. We need to address the elephant in the room.

Finally, remember that there’s a lot of information out there for patients, but it’s not all reliable. We don’t want patients pulling something out of nowhere and getting the wrong idea. Doctor Google is not an appropriate information source. Instead, you need to provide patients with reliable, well-vetted information sources throughout their treatment journey.

Conclusion

Over the past few decades, multiple myeloma survival has improved dramatically, largely due to the introduction of targeted therapies. While better outcomes are cause for optimism, associated treatments and survivorship come with a new set of challenges. Oncology nurse navigators need to consider both clinical and nonclinical factors throughout the treatment journey, including barriers to care, common diagnostics, factors in therapy selection, strategies to improve adherence, and considerations for the posttreatment period. For each of these challenges, knowledge and early intervention are essential. When all these skills are implemented together, navigators are certain to improve the safety and efficacy of myeloma treatments from each patient’s first 90 days through years of survival ahead.

References

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics About Multiple Myeloma. www.cancer.org/cancer/multiple-myeloma/about/key-statistics.html. Updated January 12, 2021. Accessed September 21, 2021.

- Padala SA, Barsouk A, Barsouk A, et al. Epidemiology, staging, and management of multiple myeloma. Med Sci (Basel). 2021;9:3.

- Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. Multiple myeloma current treatment algorithms. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(9):94.

- Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Multiple Myeloma: Optimizing Quality of Life for Survivors. https://blog.dana-farber.org/insight/2017/08/multiple-myeloma-optimizing-quality-of-life-for-survivors. Updated August 22, 2017. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- American Cancer Society. Multiple Myeloma. Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging. www.cancer.org/cancer/multiple-myeloma/detection-diagnosis-staging.html. Updated February 28, 2018. Accessed September 3, 2021.

- Gupta S, Abouzaid S, Liebert R, et al. Assessing the effect of adherence on patient-reported outcomes and out of pocket costs among patients with multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18:210-218.

- Solano M, Daguindau E, Faure C, et al. Oral therapy adherence and satisfaction in patients with multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 2021;100:1803-1813.

- Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. The State of Multiple Myeloma Care. https://avalere.com/pdfs/LLS_MM_032011_Brochure.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2021.

- Korde N, Kristinsson SY, Landgren O. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM): novel biological insights and development of early treatment strategies. Blood. 2011;117:5573-5581.

- Landgren O, Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. From myeloma precursor disease to multiple myeloma: new diagnostic concepts and opportunities for early intervention. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1243-1252.

- Muchtar E, Kumar SK, Magen H, Gertz MA. Diagnosis and management of smoldering multiple myeloma: the razor’s edge between clonality and cancer. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:288-299.

- International Myeloma Foundation. Types of Multiple Myeloma. www.myeloma.org/types-of-myeloma. Updated August 1, 2019. Accessed October 5, 2021.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for Patients: Multiple Myeloma. 2022. www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/myeloma-patient.pdf. Updated August 16, 2021. Accessed September 3, 2021.

- Tosi P, Tomassetti S, Merli A, Polli V. Serum free light-chain assay for the detection and monitoring of multiple myeloma and related conditions. Ther Adv Hematol. 2013;4:37-41.

- Bross PF, Kane R, Farrell AT, et al. Approval summary for bortezomib for injection in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3954-3964.

- Braunlin M, Belani R, Buchanan J, et al. Trends in the multiple myeloma treatment landscape and survival: a U.S. analysis using 2011-2019 oncology clinic electronic health record data. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62:377-386.

- International Myeloma Foundation. What Are MGUS, Smoldering Multiple Myeloma, and Active Myeloma? www.myeloma.org/what-are-mgus-smm-mm. Updated August 1, 2019. Accessed September 20, 2021.

- Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Ludwig H, et al. Personalized therapy in multiple myeloma according to patient age and vulnerability: a report of the European Myeloma Network (EMN). Blood. 2011;118:4519-4529.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Multiple Myeloma. Version 1.2022. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf. Updated August 16, 2021. Accessed September 3, 2021.

- Glatzer M, Panje CM, Siren C, et al. Decision making criteria in oncology. Oncology. 2020;98:370-378.

- Sweiss K. Oral antimyeloma therapy: barriers to patient adherence and tips for improvement. HOPA News. 2018;15(3).

- Cransac A, Aho S, Chretien ML, et al. Adherence to immunomodulatory drugs in patients with multiple myeloma. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0214446.

- Nestoriuc Y, von Blanckenburg P, Schuricht F, et al. Is it best to expect the worst? Influence of patients’ side-effect expectations on endocrine treatment outcome in a 2-year prospective clinical cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1909-1915.

- Maatouk I, He S, Hummel M, et al. Patients with precursor disease exhibit similar psychological distress and mental HRQOL as patients with active myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9:9.

- Gorman LM. The Psychosocial Impact of Cancer on the Individual, Family, and Society. In: Bush NJ, Gorman LM, eds. Psychosocial Nursing Care Along the Cancer Continuum. 3rd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society; 2018.

- Natale N. Multiple Myeloma Resources. Everyday Health. www.every dayhealth.com/multiple-myeloma/guide/resources. Updated July 29, 2021. Accessed September 21, 2021.

- Baileys K, McMullen L, Lubejko B, et al. Nurse navigator core competencies: an update to reflect the evolution of the role. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22:272-281.

- Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Dennis DL, et al. Survivorship care plans: a work in progress. Curr Oncol. 2014;21:e466-e479.

- Bilotti E, Faiman BM, Richards TA, et al. Survivorship care guidelines for patients living with multiple myeloma: consensus statements of the International Myeloma Foundation Nurse Leadership Board. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(suppl):5-8.